Planning for Safety

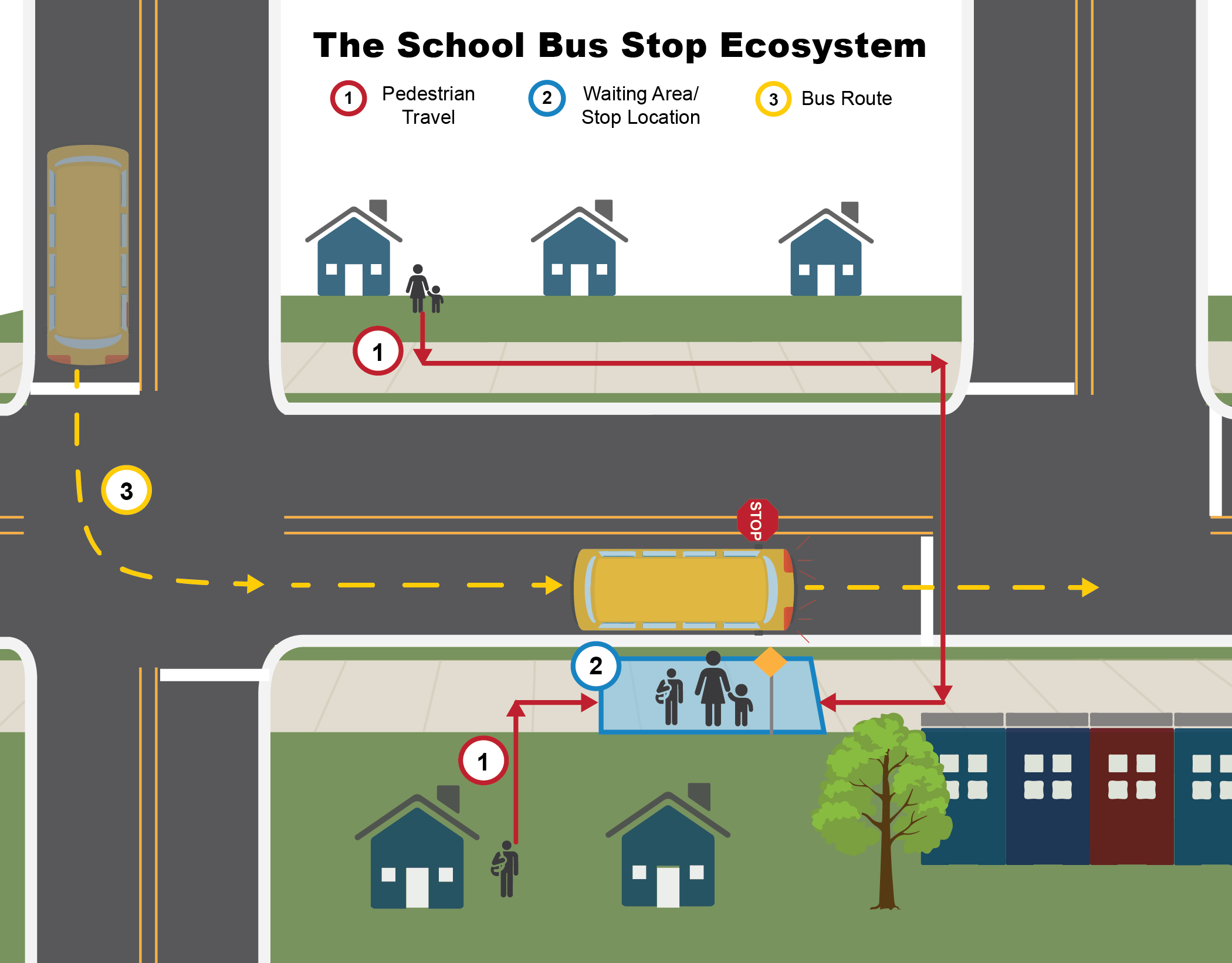

Student safety should be the top priority when determining school bus routes and stops. While riding a school bus remains the safest way to travel to school, mitigating safety risks throughout the school bus journey is essential to making this the case. Determining bus routes and stops that effectively reduce safety risks for students, and also meet operational goals, takes planning. Planning safer bus routes and stops involves processes that incorporate consideration for each of the following aspects of school travel. Planning a safer bus stop involves determining a location, but it encompasses more than that. Following state and local policies, a specific student waiting area should be identified at the bus stop location. This affects how students will access the stop and, once the bus route is known, whether students will need to cross a roadway to board.

Section Overview: Planning for Safety

Policy and Community Considerations

Preexisting policies and guidelines can influence the route and stop options available, as well as help provide guidance about what safe routes and stops look like. The nature of the community in which the routes and stops will be placed should also be considered, as each has its own unique needs and challenges. Skip to Policy and Community Considerations ->

Student Access to the Bus Stop

Many students walk to and from their bus stops, making them pedestrians. The safety and quality of their travel paths should be considered as part of the decision-making process for bus routes and stops. Skip to Student Access to the Bus Stop ->

Bus Stop Waiting Area

The school bus stop waiting area is the physical space where students wait for the bus to approach. The safety of the waiting area must be considered as transportation staff designate the bus stop. In some cases, the waiting area is on the same side of the street as where the bus stops; in others, it is across the street. Risks such as poor visibility and crossing danger should be considered as the bus stop and the bus stop waiting area are established. Skip to Bus Stop Waiting Area ->

Routing to the Bus Stop

Typically, the bus stop is considered a combination of both the waiting area and the bus stop location. Deciding where to place a stop and how to route the bus to it involves evaluating different types of information. Student safety is key while performance measures such as efficiency are also factored into how a bus is routed and where a stop is located. Skip to Routing to the Bus Stop ->

Planning with Software

Using computer software to help with the development and maintenance of school bus routes has become a standard practice for most large school districts. Just as many individuals rely on a vehicle-based or smartphone-based navigation system when traveling, school bus routing relies on similar maps that are based on a geographic information system technology. Computer algorithms can calculate the appropriate school of attendance based on a residential address and can similarly assist with the process of determining eligibility for transportation, assigning students to bus stops, and creating bus routes that safely and efficiently link those stops together. Skip to Planning with Software ->

Developing and Implementing Procedures

Given all the items to consider, planning bus routes and stops can feel overwhelming at times. Knowing about potential challenges ahead of time and making plans early about how to manage them can help save time and energy in the long run. One of the best resources can be using existing procedures developed by others and adapting them to meet your present needs. Skip to Developing and Implementing Procedures ->

Information Exchange

In addition to resource links in this toolkit, ongoing collaboration with other school transportation practitioners (i.e., through state and national associations) can help make the school bus routing and planning process easier. Skip to Information Exchange ->

The graphics in this section are for illustrative purposes only and are not to scale or meant to represent all traffic control elements that should be present.

Policy & Community Considerations

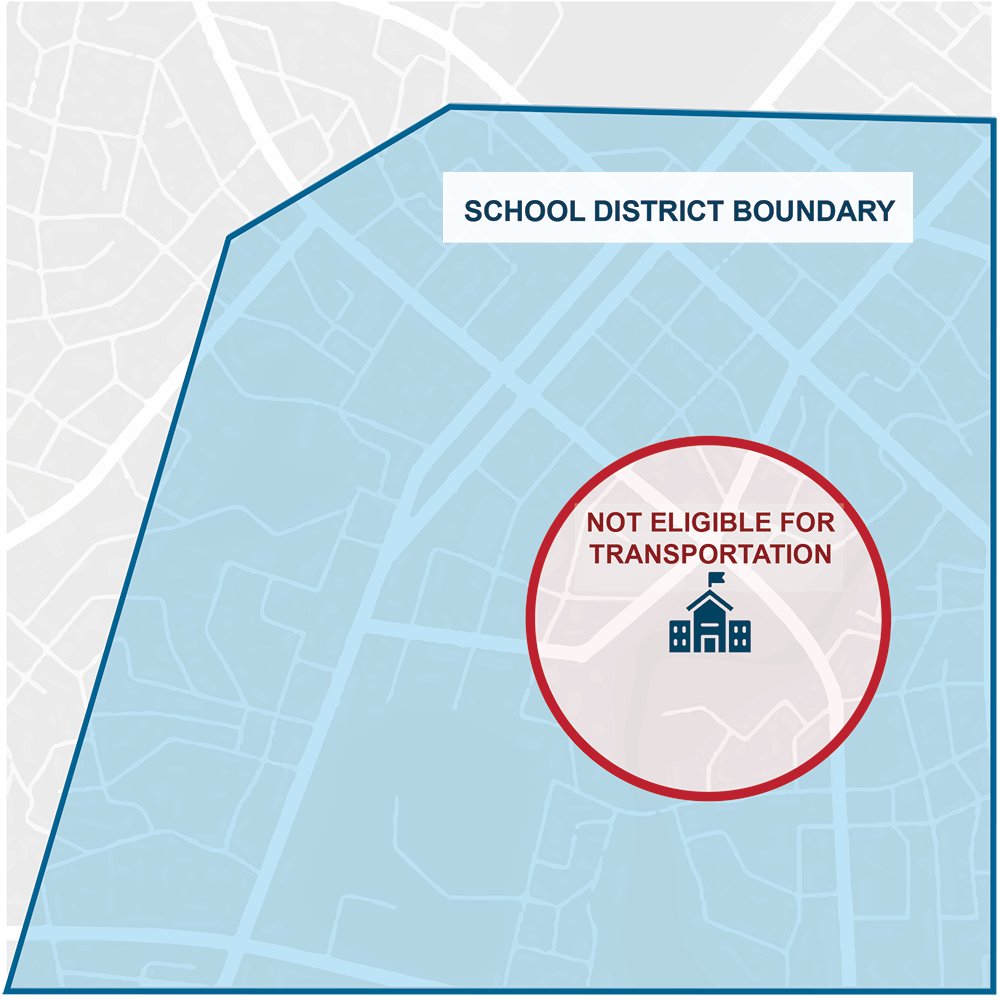

State and local policy can dictate the limits of the school district attendance boundary, and which addresses inside that boundary are eligible for transportation. This is an example of how similar policy may also designate an area around each school in which students are not eligible for transportation.

Policy

School bus route and stop decisions are not made in a vacuum – there are many policies and guidelines that may influence stop and route options available. It is important to identify and consider applicable state and local policies before determining locations. Some school districts may also have policies, official or unofficial, that inform how school bus routes and stops are developed. Examples include preexisting rules about which students are eligible for school bus transportation and policies that describe which student grade levels are allowed to wait at a bus stop together.

The Common State and District Policies section provides more details on the types of relevant policies and how they may affect school bus routing and stop decisions. An overview of the stakeholders involved in the decision-making process is available in the Decision-Making for School Transportation Routes and Stops section.

State and local policy can dictate the limits of the school district attendance boundary, and which addresses inside that boundary are eligible for transportation. This is an example of how similar policy may also designate an area around each school in which students are not eligible for transportation.

Community Variations

Specific needs for routes and stops may vary by community type. Rural communities typically have less safe walking conditions due to higher-speed roadways, a lack of paved sidewalks, and larger areas of undeveloped land. Additionally, the way houses and land are distributed may require students to walk farther to their bus stops than those in more urban environments. Walking conditions in underserved areas, such as low-income communities, may be more hazardous due to a lack of acceptable transportation facilities and/or road conditions. The threat of non-vehicle-related injury or harm may also be higher in low-income communities compared to higher-income communities. Those making school bus route and stop decisions should strive to develop plans that consider these issues to provide safe school travel options for all students.

Educating the School Community

Another way to improve safety on the path a student takes from home to the school bus is to share pedestrian safety tips. Parents and guardians can play an important role in student safety by accompanying students to stops and reinforcing safe behavior. In addition to numerous resources in the Helpful Resources section, NHTSA provides simple guidance you can use to educate your school community.

Student Access to the Bus Stop

Students riding school buses are traveling as part of a larger transportation system that should be considered when determining routes and stops. While some students may be driven to and from their bus stops, most students walk. These students are not just bus riders but are also pedestrians who may be actively moving from several directions as they travel to and from bus stops. As a pedestrian, a student’s safety may vary based on the walkability of his or her travel path.

Students riding school buses are traveling as part of a larger transportation system that should be considered when determining routes and stops. While some students may be driven to and from their bus stops, most students walk. These students are not just bus riders but are also pedestrians who may be actively moving from several directions as they travel to and from bus stops. As a pedestrian, a student’s safety may vary based on the walkability of his or her travel path. School district personnel should consider the environment between the student’s location of origin and the school bus stop waiting area and may make decisions based on the age of the student involved. The following are key considerations.

Roadway Characteristics

The characteristics of the surrounding roads matter because the roads students must walk along or cross can put them at risk of being involved in crashes. For more information on specific considerations and recommendations, see Roadway Characteristics and Intersections.

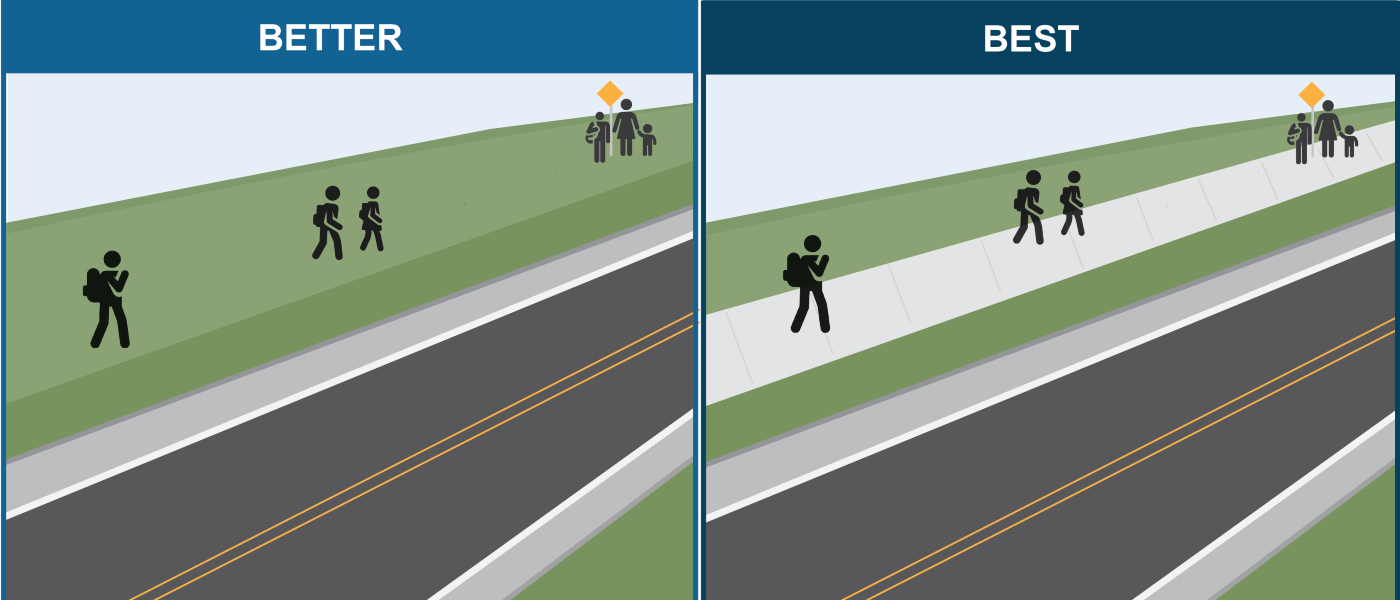

Walkable Infrastructure

The quality of walking paths connecting students’ homes and roadsides can determine their level of exposure to the surrounding roadways and risk of injury. Stops connected to designated walking paths that are well-defined and well-maintained are ideal. The following factors should be considered when determining whether a path is walkable.

Routes that include opportunities for students to use established paths (such as sidewalks) that are physically separated from the roadway can improve safety, particularly in areas with high-speed roadways.

Often an established path is through a grassy area away from the road, but it is best when set out via pavement or gravel, for example.

Traveling clearly defined pedestrian paths can reduce the likelihood that students will take alternative routes that could pose other safety risks. Traveling maintained paths is more reliable than alternative routes that can be prone to flooding, erosion, and other weather-sensitive issues that can create safety risks.

While not available to all students, a defined sidewalk path to the bus stop is best.

Paths that include sidewalks with heavily broken pavement, rough terrain, or other issues can create hazardous walking conditions. Traveling well-managed paths can reduce a student’s risk of falling, for example.

Clearly defined pedestrian paths include sidewalks and other types of maintained walking facilities. A path to a stop that includes partial sidewalk coverage should not be considered as safe as one that provides sidewalk coverage from the front door to the bus stop. In communities where this type of infrastructure is not present, students may have to walk along a roadway. In this case, students should use a protected corridor and walk along the roadway in the direction facing traffic. Student age needs to be considered when developing stops that require a student to walk along a roadway. For example, high school students may be able to walk along roadways more safely than students in elementary grades.

Here, the student driveway is in a blind curve, and the sidewalk is not safely accessible. The bus stop could be placed at the student driveway on the bus’s right side. However, sight distance for motorists approaching from the rear is not ideal.

Rural roads often have limited options for walking travel paths, complicated by ditches, vegetation, etc., beside the road.

Walking Environment

Even if the infrastructure on a student’s path to and from the school bus is considered safe, the environment surrounding the path may present safety risks. School bus stop locations that require students to encounter potential safety risks should be identified and considered when locating bus stops. Risks associated with Crossing Roadways, Railroad Crossings, certain Roadway Characteristics and Intersections, and other Potential Hazards are of particular concern for a student travel path.

For more information about planning for safe routes to and from the bus stop, refer to resources from the National Center for Safe Routes to School.

Bus Stop Waiting Area

The bus stop waiting area is the physical space where students wait and may not always be consistent with the road description of the bus stop itself.

The bus stop waiting area is the physical space where students wait for the bus to arrive. In some cases, this waiting area is across the street or at another designated location away from the bus stop location, or the designated point where the driver stops. An extension of a school bus route, the bus stop is a combination of both the waiting area and the bus stop location. There are many safety risks that need to be managed at the stop. Specific considerations include the following.

Waiting Area Space

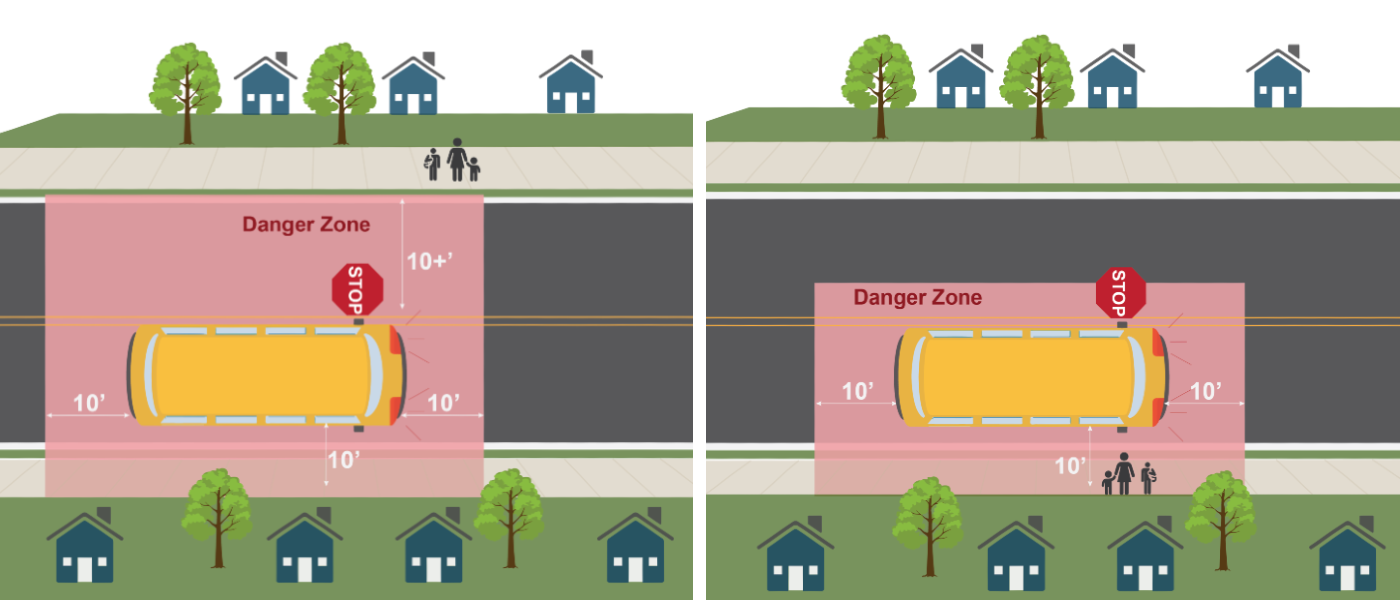

The size of the waiting area and how it is used matters. The waiting area should be designated in a location that keeps students out of the danger zone surrounding the school bus as the bus arrives at the bus stop and as they wait for the bus.

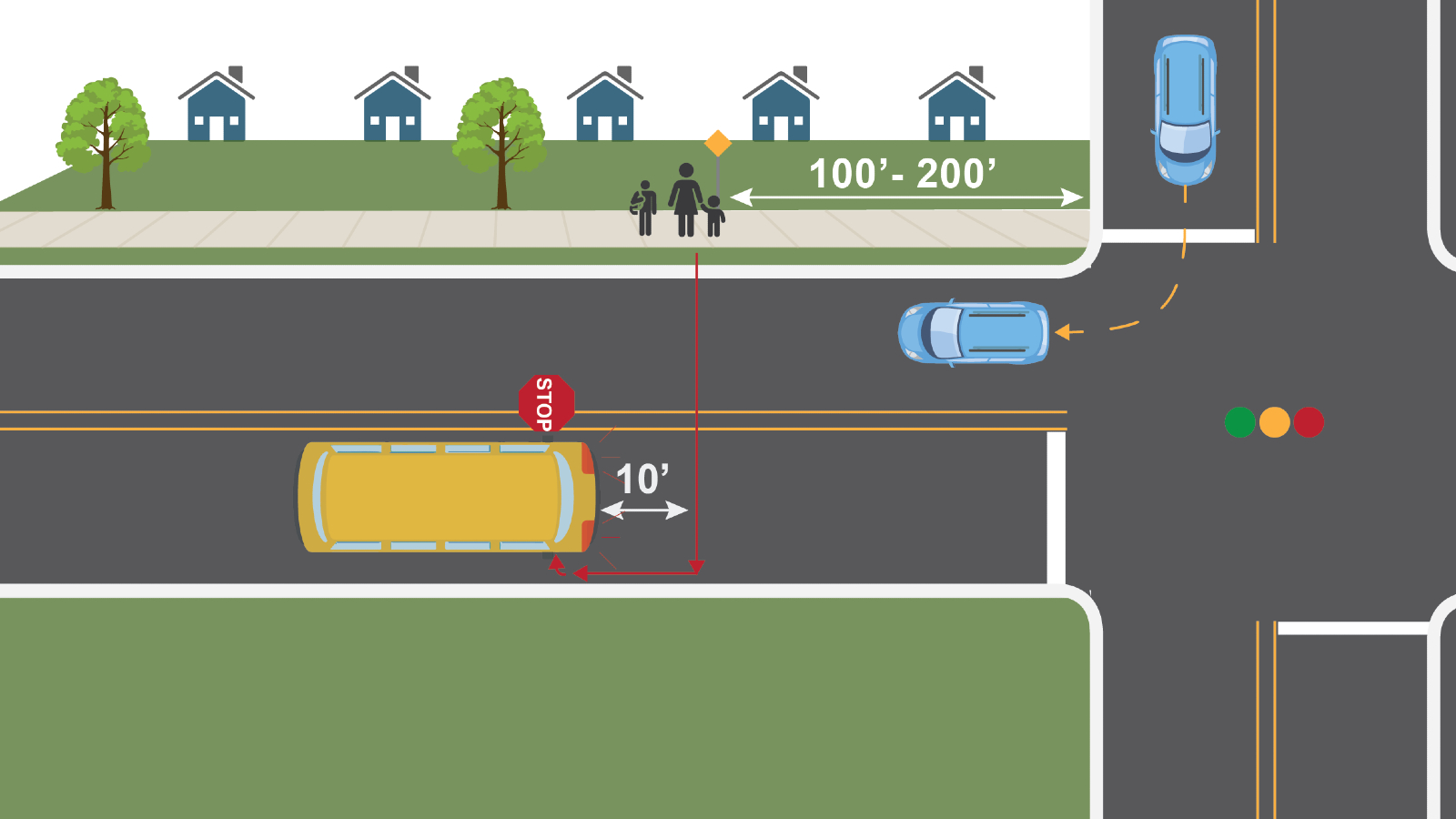

The bus stop waiting area must provide room for students to wait in the morning, to exit the bus in the afternoon, and to step 10 feet away from the school bus before walking home.

Students should be taught to stay out of the School Bus Danger Zone - 10 feet on each side of a stopped school bus. Where students have to cross the street to board the danger zone extends to their bus stop waiting area, as shown above.

The safety of a bus stop is affected by the number of students that will board/exit the bus at the stop. Stop locations should not be considered unless there is enough waiting area to fit the number of students assigned when routes are prepared. Discipline and safety issues, like proximity to the nearest lane of traffic, should be considered. The grade levels of students at the stop may also influence decision-making.

Visibility

The most often mentioned characteristic of a safe school bus stop in existing documents and checklists is visibility, which is essential from several perspectives. Visibility of the stops and students by approaching motorists, visibility of students and approaching motorists by the school bus driver, and the ability of students to see the approaching school bus while staying safely out of the roadway should also be evaluated.

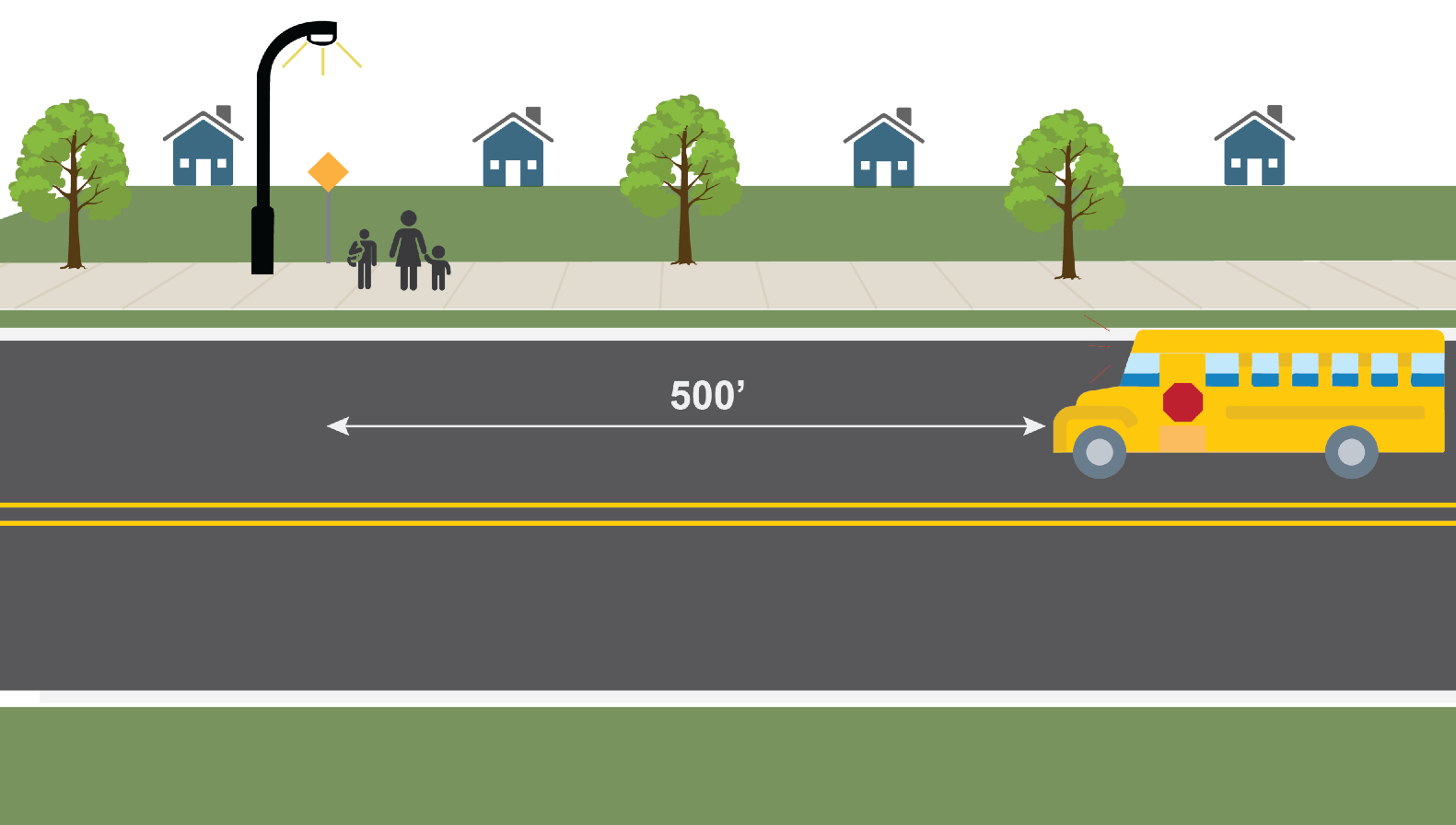

Particularly during winter months, it is likely that some students will be boarding or disembarking the school bus in the dark. Lighting at a school bus stop is a great benefit to the overall visibility. All else being equal, locating a school bus stop within the lighted area beneath a street lamp is preferable. In rural areas, this becomes more challenging and is sometimes simply not possible.

In the illustration above, rather than locating the stop central to all residences, the stop is placed at a location where lighting is present.

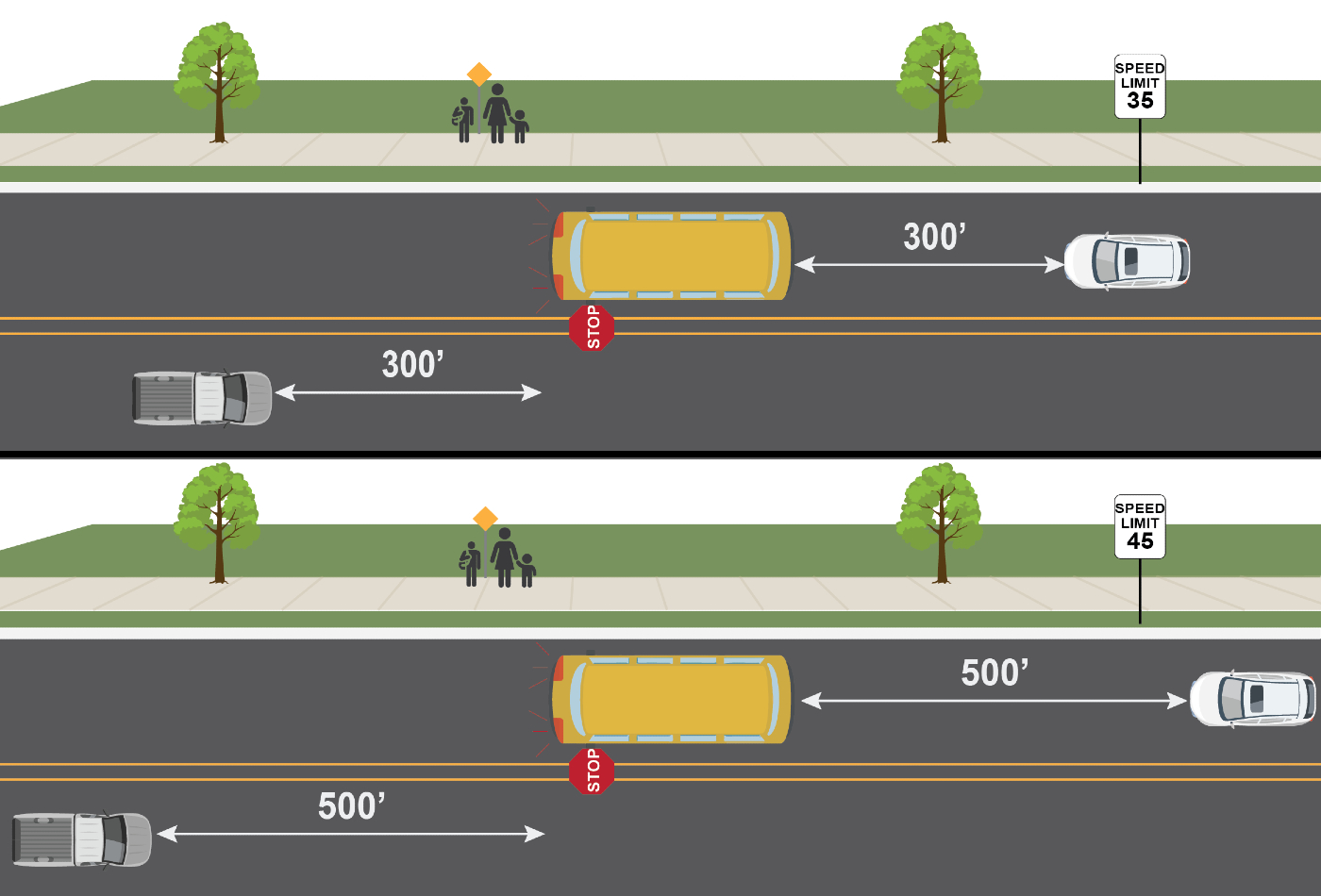

For student safety, it is important that stops are located in areas that, where possible, provide motorists enough visibility of the stop and, when present, visibility of the stopped school bus. Required visibility may vary depending on the speed limit, which affects driver reaction times. The American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO) provides A Policy on Geometric Design of Highways and Streets, which includes a table of stopping sight distances on level roadways that vary by design speed. AASHTO also provides additional tables based on varying degrees of vertical and horizontal curvature. However, individual school districts may provide specific sight distance requirements based on speed limits, which are typically more conservative than the sight distances provided by AASHTO. The following graphic represents sight distances that are typical of those provided in several state and local school transportation sources, highlighting the need for longer sight distances in higher-speed areas.

These examples represent sight distances typical of the state and local sources reviewed, highlighting the need for longer sight distances in higher speed areas.

Many obstructions can affect visibility at the school bus stop, from several points of view. Motorists should be able to see students at the stop and to see a school bus stopped ahead. School bus drivers should be able to see students at the stop and to see the approach of oncoming traffic. Students should be able to see the approaching school bus and traffic from all directions. To achieve these goals, bus stop locations should minimize the impact of visibility caused by vegetation (like trees and shrubs), parked vehicles, signs, light poles, structures, etc.

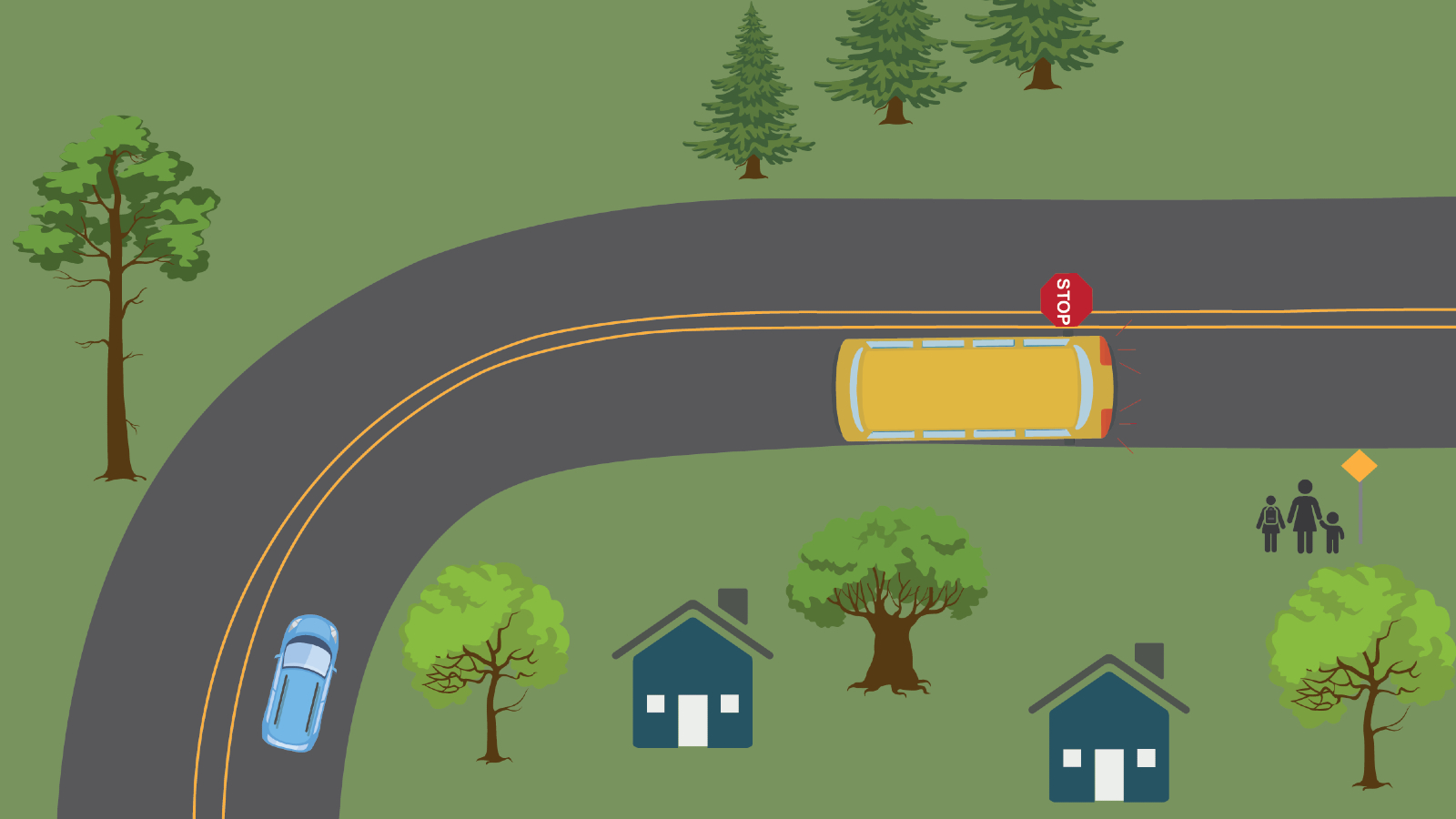

In this example, the trees and houses may prevent students from seeing vehicles approaching from around the curve and vice versa.

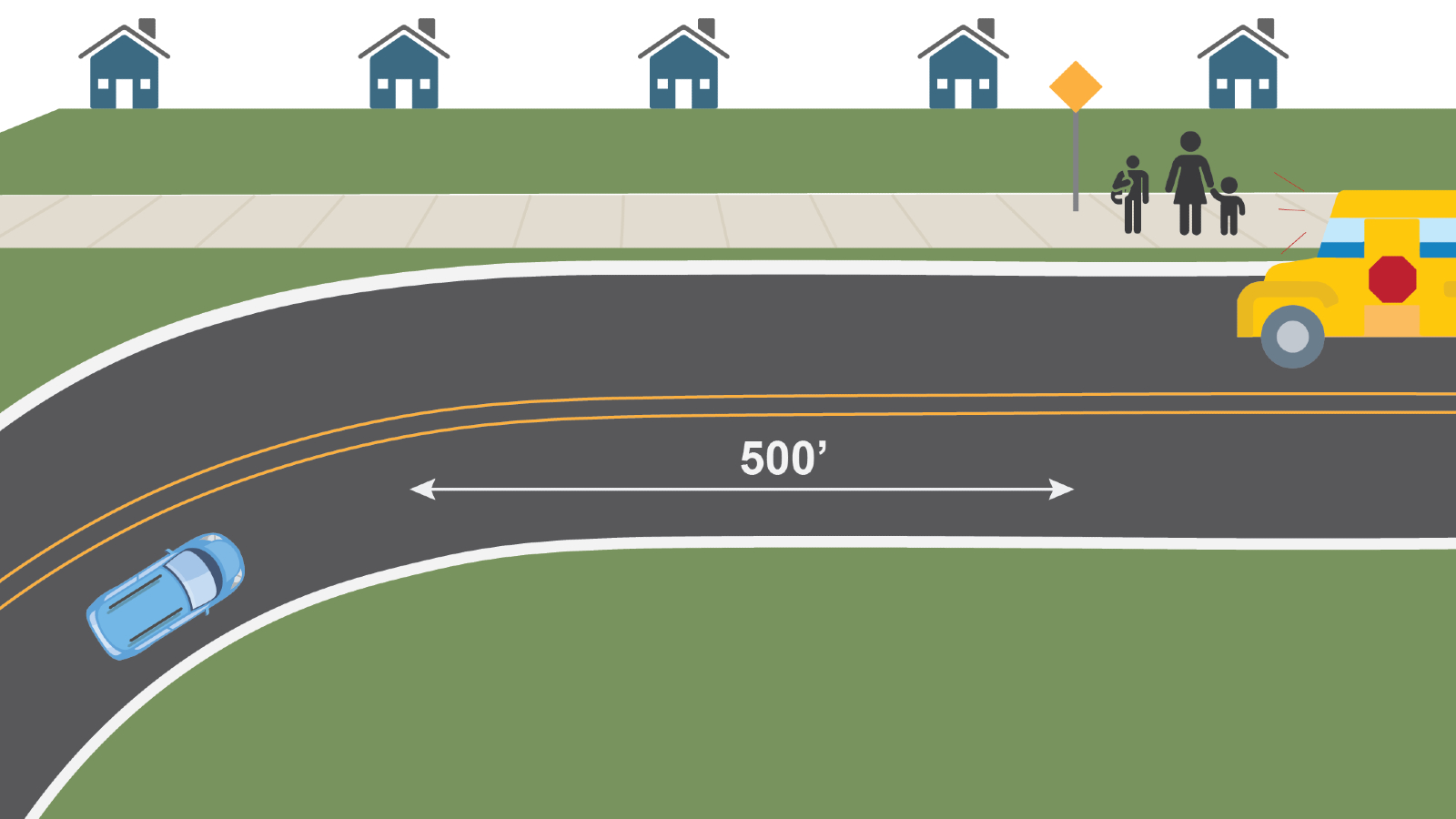

The layout of the road itself can lead to motorist visibility challenges. Geography like steep hills and roadway design elements like curves can impede a driver’s ability to see an upcoming school bus or school bus stop. When a stop location near such visibility challenges results in a sight distance of less than 500 feet, consider contacting the state or local department of transportation to add signage to warn drivers.

A clear, straight-line sight distance of 500 feet allows approaching traffic to react to a stopped school bus and safely come to a stop.

If visibility is such that approaching motorists cannot see the school bus stop, a “School Bus Stop Ahead” sign should be posted. This should be done in consultation with the state or local DOT, as it is important not to post too many signs so that they blend into the background and go unnoticed by motorists. See Helpful Resources for more information on coordinating with state or local DOTs for the installation of “School Bus Stop Ahead” signs.

Surrounding Environment

The environment surrounding a school bus stop can affect the safety of the stop itself. School bus stop locations that are near the following potential safety risks should be identified and considered when developing bus routes and stops, as much as possible:

- Crossing roadways: see Crossing Roadways for more information.

- Intersections: Bus stops should be moved away from road intersections, especially on roadways with higher speed limits (e.g., greater than 35 mph). See Roadway Characteristics and Intersections for more information.

- Railroad crossings: Bus stops should be at least 300 feet from a railroad crossing. See Railroad Crossings for more information.

- Non-vehicle safety threats: Known safety threats such as known high-crime areas, potentially dangerous wildlife or animals, etc., should be avoided. See Non-Vehicle Threats to Physical Safety for more information.

- Other potential hazards: See Potential Hazards for more information.

Routing to the Bus Stop

Numerous factors are considered when deciding where to place a stop and how to route the bus to it. For many districts across the country, initial recommendations usually begin with examining where stops have been placed historically and using software to identify the optimal routes. Considerations for routing software are discussed in detail as part of the Planning With Software section. The following items should be considered when identifying where to place a stop to reduce safety risks for students.

Route Design and Efficiency

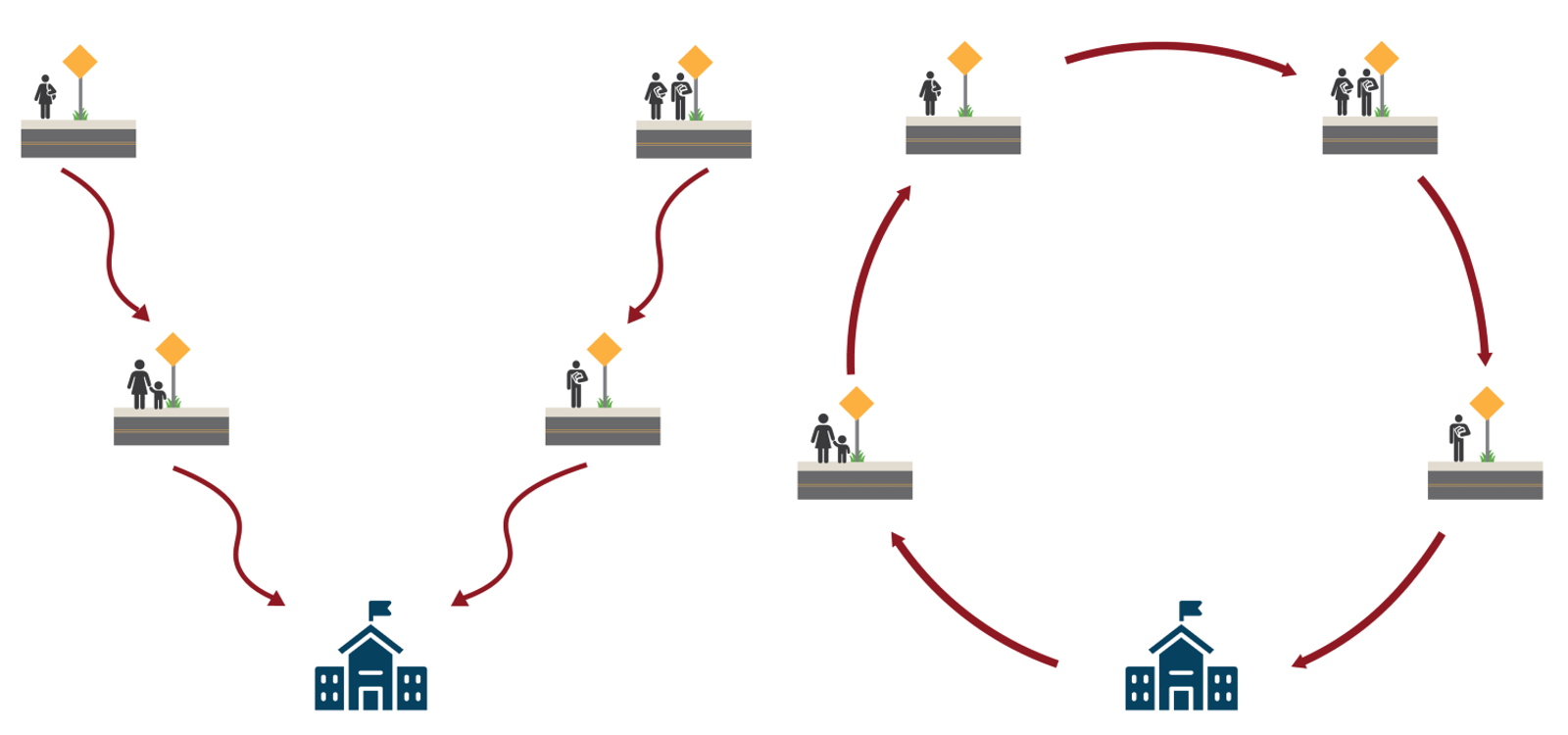

The basic process of designing a school bus route starts similarly to designing a route for package delivery. It is essentially what is known as the Traveling Salesman Problem: What is the most efficient way to visit a given number of locations (such as school bus stops)? The most common designs are circular and shoestring routes. Circular routes begin at the school, visit a group of stops in a circular pattern, and then return to the school. A circular route may be run in the same direction in the afternoon (which could balance out bus riding times for the day), or in reverse in a “last on, first off” pattern. A shoestring route begins at a point away from the school and works its way back to the school, picking up students along the way.

Examples of shoestring route (left) and circular route (right) types.

It is generally accepted – and sometimes set in state and local policy – that school bus routes should be designed in a way to promote efficiency of operation. Efficiency includes cost as well as service level measures such as on-time arrival. While safety should always be a top priority, there is a natural tension between efficiency and safety. A route involving more student crossings may be significantly more efficient from a cost perspective than one involving more right-side pickups. It is difficult to balance these tradeoffs, and transportation departments must develop practices to address this tension for all students.

Route Design and School Bus Stop Safety

The direction from which a school bus will approach a given bus stop is not known until the route is developed. This consideration is especially important for situations involving roads that students may not cross – either to board the bus or to access the bus stop. Route design must consider not only the order of stops but the direction of approach on hazardous roads, reducing situations in which students must cross roads.

Following an investigation of three fatal crashes involving students crossing the road to board the bus, the NTSB recommended that NASDPTS, NAPT and NSTA, “Inform your members of the circumstances of the Rochester, Indiana; Baldwyn, Mississippi; and Hartsfield, Georgia, crashes, and urge them to minimize the use of school bus stops that require students to cross a roadway (especially a high-speed roadway) and to, at least annually, and also whenever a route hazard is identified, evaluate the safety of their school bus routes and stops (H-20-15).” Consistent with this recommendation, some school district policies or operating procedures require door-side bus stops, especially for younger students. Recognizing that 100% compliance is rarely practical, careful evaluation of bus stops requiring students to cross should be conducted.

There are many other common safety-related routing practices. One example is the minimizing of left turns when developing school bus routes. A NHTSA study reports that turning left is a leading pre-crash event in 22% of all crashes, compared with turning right (1.2%). Avoiding left turns can also increase efficiency by reducing waiting times at intersections. When safety objectives conflict, such as the inability to both eliminate a left turn and also make a door-side stop, school district transportation staff must weigh the safety benefits and make an informed decision when planning a route.

Route Hazards

In addition to the direction of travel of the school bus, the safety of students at the school bus stop can be affected by known route hazards at, around, or approaching the stop. Route hazards are most likely known by the regular driver of the route but may not be obvious to a substitute driver. Route hazards may include Roadway Characteristics and Intersections, Railroads Crossings, or other types. For details about hazards and suggested processes for mitigating them, see Potential Hazards.

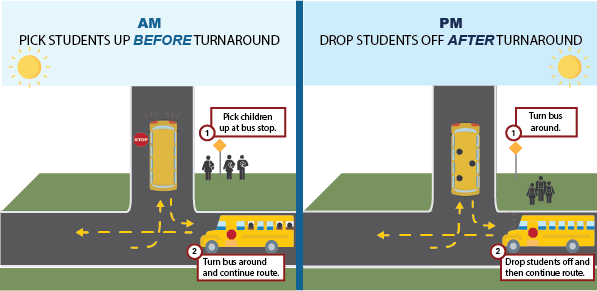

Route Turnarounds

A bus route that calls for a bus to travel a particular road and then turn around after a stop, returning in the direction from which it came, is a routing practice to be avoided when possible. Sometimes this practice cannot be avoided for reasons such as road configurations and student residences. In these cases, these factors should be considered or addressed before determining if it is safe for a school bus to perform a turnaround:

- Signage for turnaround: Road signs making motorists aware that there is a school bus turnaround location ahead can improve safety.

- Speed limit sign: A clearly visible speed limit sign for motorists approaching the turnaround location can help reduce speeding in the area.

- Space to back up and turnaround: Physical space for the bus to perform the turnaround is essential.

- Sight distance: The location of the turnaround should ensure that motorists approaching in all directions can see the school bus as it performs the turnaround.

Ensure that students are on the bus when it is backing up or turning around near a school bus stop. In the morning, the stop should be before the turnaround. In the afternoon, the turnaround should be made before the bus stop.

Planning with Software

Computer software is a valuable tool for routing and can consider student and bus stop locations, travel turn restrictions, walkable paths, and allowable crossing environments.

Computers can help store large amounts of information like mapping details, and computer algorithms can calculate distances, determine student eligibility for transportation based on a student’s address, and assign students to the closest bus stops for their schools. A number of companies provide school bus routing software used to conduct these processes, but not all software approaches the school bus route and stop the same way. Because of this, it is important to have rules in place to prevent stop assignments resulting in unsafe pedestrian paths and other safety risks.

In addition to helping assign students to stops and bus routes, transportation software systems can help with planning school attendance zones, GPS tracking of buses, and optimizing school bus routes. However, no computer algorithm is perfect, and software outputs are only as good as the data school planners add to the system. More accurate student locations and the designation of safety rules within a school district’s routing system are essential for planning safer stops and routes.

Pedestrian Path

A computer system can keep track of the pedestrian travel path from point A to point B. School districts should work with their technology providers to best determine how to designate which bus stops are safely accessed from which student residences (or other designated locations). This consideration may change by student grade levels. For instance, is a student allowed to walk along a given roadway to reach the bus stop location? Is the student allowed to cross the road to reach the assigned bus stop location on this roadway? In general, the same rules apply when the bus stop waiting area is allowed to be located across the road from where the bus opens its door. These rules also apply to pedestrian travel paths for students approaching the bus stop.

Once students are assigned to bus stops, the transportation department links those stops together into bus routes for transportation to school. These are referred to as routes, although some may refer to them as “linked stops,” a “run,” or a “trip,” and would consider a route to cover multiple runs, both for the morning and afternoon.

Managing Safety Risks

When safety is at stake, safe school travel involves more than just the location of the bus stop. In a situation in which children cannot safely cross the street to board the bus, it is key for the school bus routing software to make sure the bus is approaching from the proper direction. In routing software, streets can have features, and those features can include whether students are allowed to cross.

Crossing criteria can vary from state to state but in general, they are based on the number of lanes and the speed limit. Stops and travel along divided roads, divided highways, multilane roads, etc., must be reassessed for student boarding once the direction of travel is known. This is not just a matter of coding a bus stop to be on the right side of the road, because doing that could create a situation in which students are required to cross that same road before the bus arrives. Such a situation can present additional safety concerns. Routing software can consider these features, often through an iterative process. Without restrictions, the most efficient sequence may be going from stop A to stop B to stop C. But when safety and allowable crossings are considered, it may be best to travel A-C-B because that will allow the bus to be on the right side of the road approaching stop B.

Substitute school bus drivers, in particular, benefit from turn-by-turn directions and passenger lists produced by school bus routing systems.

Information for the Driver

Whether on a Mobile Data Terminal or a paper route sheet, computer routing systems can maintain and provide drivers with important safety information. Typically, the order of stops and specifics related to when to turnaround are included in basic routing instructions, along with designations of stops as right-side pickups. Documented route hazards and details like the storage area at a railroad crossing, blind curves, and narrow bridges, can be included in the route sheet as well. Because the route sheet is the primary means of telling the driver about the route, it is critical to prepare the data so that the route sheet is complete. Route sheets are especially helpful to substitute bus drivers who may not be aware of the unique characteristics of a given route.

Developing and Implementing Procedures

The school bus route and stop planning process is complex and can feel overwhelming at times. Developing plans early, including procedures to help guide the process, can save time and energy in the long run. Procedures can include any practices that help provide structure to the planning process, like guides, checklists, forms, etc. Implementing procedures consistently and building off existing examples can also help relieve some of the challenges that come with planning.

Development

Various components of the bus stop creation and review process are included in existing policies, as discussed in Policy and Community Considerations. It is generally up to school district transportation staff to create those policies and to incorporate them into daily procedures. Following these policies consistently is also key. To help with this, a school district should have a well-defined, written procedure for creating and reassessing school bus stop locations.

There are many stakeholders invested in school bus route and stop planning. Acknowledging and engaging these individuals and groups early can help ensure a smoother planning process with more community buy-in.

When establishing written operational procedures, codified or not, it is helpful to gain input from a wide range of perspectives. Suggested representatives to include are as follows:

- Parent representatives

- Local law enforcement

- School administration

- Transportation department administration

- Bus routers

- Municipal or regional transportation (roads) department

- School bus drivers

- School bus driver trainers

- School board members

One way to involve local law enforcement in school bus communication is through safety briefings.

This group should be educated to consider all facets of the school bus stop ecosystem:

- Accessing the stop from the student’s home

- School bus stop waiting area

- Bus routing, its safety implications, and review of hazards

This toolkit provides a starting point for the working group but cannot include every situation – especially those that may be unique to the school district. For more information, see Planning for Safety.

Addressing Community Concerns

School districts need to have well-defined criteria and procedures for establishing bus stops to ensure safety and ensure the placement of stops is easily justifiable to community members. There are times when a parent, guardian, caretaker, or other concerned community member may wish to have a stop evaluated for a perceived safety concern. Examples include concerns about not being able to see a child at a bus stop or a child having to walk a long distance to reach a stop. Districts should define the process community members should take to have a school bus stop evaluated. School districts vary considerably on how this is done — some require form(s) to be filled in while others may only ask for a phone call. Community members should be able to easily find information on how to start the process, as well as any required forms.

Responsibilities at the Bus Stop

The bus stop is where a shift in responsibilities occurs between the various stakeholders in pupil transportation services. The district is responsible for ensuring the establishment of safe stops and routes in accordance with state and federal laws, but the parents and students have a responsibility to reach the stop and wait for the bus in a safe manner. No matter how well bus stops and routes are designed, oversight of a responsible person cannot be substituted, considering that students are a range of ages and capabilities. It is reasonable to educate parents about their responsibilities, but ultimately traveling to the stop is part of the school bus route and stop process that must be considered by the school district.

As an example, Volusia County (FL) Schools include a list of FAQs on its transportation page, some of which help to educate parents about school bus stops and serve as examples to consider when communicating to parents. Some of the FAQs include the following:

- Why does my child have to walk so far to the bus stop?

- Who is responsible for student safety at the bus stop?

- How are bus stop locations identified?

Similarly, the Northshore (WA) School District includes parent responsibility in the FAQ on its transportation web page, including a statement that, “Parents are responsible for their children until they board the bus.”

The Helpful Resources section of this toolkit provides some examples of approaches that school districts take for communicating guidelines and policies.

School districts need to have well-defined criteria and procedures for establishing bus stops to ensure safety and ensure the placement of stops is easily justifiable to community members. There are times when a parent, guardian, caretaker, or other concerned community member may wish to have a stop evaluated for a perceived safety concern. Examples include concerns about not being able to see a child at a bus stop or a child having to walk a long distance to reach a stop. Districts should define the process community members should take to have a school bus stop evaluated. School districts vary considerably on how this is done — some require form(s) to be filled in while others may only ask for a phone call. Community members should be able to easily find information on how to start the process, as well as any required forms.

The bus stop is where a shift in responsibilities occurs between the various stakeholders in pupil transportation services. The district is responsible for ensuring the establishment of safe stops and routes in accordance with state and federal laws, but the parents and students have a responsibility to reach the stop and wait for the bus in a safe manner. No matter how well bus stops and routes are designed, oversight of a responsible person cannot be substituted, considering that students are a range of ages and capabilities. It is reasonable to educate parents about their responsibilities, but ultimately traveling to the stop is part of the school bus route and stop process that must be considered by the school district.

As an example, Volusia County (FL) Schools include a list of FAQs on its transportation page, some of which help to educate parents about school bus stops and serve as examples to consider when communicating to parents. Some of the FAQs include the following:

- Why does my child have to walk so far to the bus stop?

- Who is responsible for student safety at the bus stop?

- How are bus stop locations identified?

Similarly, the Northshore (WA) School District includes parent responsibility in the FAQ on its transportation web page, including a statement that, “Parents are responsible for their children until they board the bus.”

The Helpful Resources section of this toolkit provides some examples of approaches that school districts take for communicating guidelines and policies.

Implementation

Once the procedure is developed and documented, an implementation schedule should be established and followed. Transportation departments can unintentionally neglect to review bus stops and routes consistently and regularly amid other priorities, but implementation is an essential part of a successful procedure. Pupil transportation is continually evolving and ongoing. It can be difficult to reestablish all bus stops subject to newly enforced or newly adopted criteria, such as those recommended in this toolkit. Implementing a procedure when a new bus stop is established, or an existing bus stop is called into question, can help reinforce the importance of the procedure.

While a review of a bus stop often originates from parent or guardian concern, school bus drivers may also raise concerns based on their observations. Bus drivers should also be charged with pointing out safety issues on their existing routes. Educating bus drivers on the details of established procedures will encourage and help them to follow the procedures. See the Guidance Documents subsection of Helpful Resources for information on NHTSA’s School Bus Driver In-Service Curriculum.

The guidance provided in this document focuses on the initial designation of bus stop locations and creation of bus routes, but a systematic review of every stop in use is another important practice that should be done annually. Typically, this begins with a bus driver’s initial screening of bus stop safety (likely when documenting route hazards). Questions and observations are documented and submitted to a supervisor for review. Depending on the situation, the supervisor may perform an onsite evaluation in much the same way as reviewing a bus stop safety issue reported by a parent. Training is required so the appropriate staff are aware of the safety criteria to consider.

Most school districts serve students from a variety of backgrounds and circumstances. Similarly, the school bus stop locations that serve students represent a variety of characteristics on the safety spectrum. Student safety must be considered regardless of geography or the socio-economic makeup of a neighborhood. For example, a policy dictates that a bus stop should not be located where the bus deviates into private roads. That same policy should be applied to a mobile home park, apartment complex, or gated community. Safety considerations based on the roadway and crossing guidance, discussed throughout this toolkit, must be applied to all students.

Many students with special needs have individual transportation plans, which includes the designation of the school bus stop. As such, exceptions must often be made to the general rules of establishing bus stop waiting areas to best serve the student, even resulting in home stops located at the end of or in students’ driveways.

To the extent that a student with a disability can be provided transportation that is substantially the same as students without disabilities, the guidance found in this document may well apply. However, as individualized transportation is planned, the primary consideration is developing a transportation plan that meets the individual needs of the student while complying with the applicable local, state, and federal laws and requirements.

Preschool students and students with individual transportation plans are often assigned a school bus stop at their homes to accommodate their special needs.

“The term special education means, ‘specially designed instruction to meet the unique needs of a child with a disability.’ When transportation is required to provide access to such instruction, it is considered a “related service.” As part of the mandate of a Free Appropriate Public Education (FAPE), related services are required when determined necessary to assist a child with a disability to benefit from special education…The safe transportation of a child with special needs requires a plan that considers and adapts the transportation services to the individual needs of the student. This plan is called an “Individual Transportation Plan” (ITP) and functions as a sub-part of the IEP (Individualized Education Program) when transportation is a related service.”

-“NATIONAL SCHOOL TRANSPORTATION SPECIFICATIONS AND PROCEDURES,”

NATIONAL CONGRESS ON SCHOOL TRANSPORTATION, 2015

Resources

Many of the considerations discussed in this toolkit can be integrated into checklists and policy guidelines. The most common checklists and forms are (1) those used by a school district in evaluating a new or existing bus stop and (2) those used by parents and others to request a change in bus stop location. A few examples are outlined in the Helpful Resources section.

Information Exchange

Pupil transportation services are complex, involve a variety of stakeholders, and are governed by local, state, and federal policies. No single decision-maker is expected to have all the solutions to the challenges associated with the establishment of safe bus stops and routes. Working with the local school district and experts at the state and federal levels is key to providing safe and efficient pupil transportation services. Information exchange between stakeholders at all levels is critical for keeping up with best practices. There are several ways to engage with other stakeholders, including the following approaches.

Most states have an association for pupil transportation services that can serve as a resource for navigating both federal and state laws. Getting involved with your state’s association will provide opportunities to meet other professionals dedicated to the safe transportation of pupils and provide a forum where information exchange can occur.

For questions about state laws, contact your state’s director of pupil transportation.

Developing relationships at the local level will provide access to local knowledge critical to the establishment of safe stops and routes.

For local traffic safety questions: Community professionals, such as local law enforcement, traffic planners, and Safe Routes to Schools advocates can serve as additional resources for planning stops and routes. They will have a perspective on local traffic patterns, local hazards, and various other safety concerns that state and federal partners may not.

It is important to establish relationships with not only local partners, but state and federal partners as well. School districts are unique and often come with their own sets of challenges when it comes to establishing safe stops and routes. Despite these challenges, given the thousands of school districts across the United States, it is likely others have faced similar situations before. Attending state and national transportation conventions to network with other transportation professionals can help you find solutions to your transportation issues.

Attending conferences and other networking events can provide opportunities to learn from others in the school bus routing and planning community.

Getting involved in professional associations will allow you to stay up to date with best practices and network with other professionals. State and national groups include networks of professionals who deal with pupil transportation every day. The National Association for Pupil Transportation, the National Association of State Directors of Pupil Transportation Services, and the National School Transportation Association are examples of such associations at the national level. State and regional organizations provide similar opportunities.

For questions related to school bus safety and current school bus initiatives, contact your state director of pupil transportation.

For more information on school bus stops and routing stakeholders, see the Decision-Making for School Transportation Routes and Stops section of this toolkit.

Additional Information

Policies specifically related to the following issues can commonly influence route and stop decisions. These types of policies should be examined and understood as part of the route and stop planning process. Not all of these policies will apply to your district, but they should be considered.

Policy Issue & Description

Bus stop property owner: District practice when a bus stop waiting area is on private property and there is a need for owner notification or permission.

Distance from school for transportation: Rules about who is entitled to school bus transportation based on the distance a student’s home is from the school site.

Distance from stop: Rules that dictate how far a stop can be located from a student’s home, such as “a bus must pass within 1 mile of students eligible for transportation.”

Driver involvement in bus routing changes and bus stop review: While the school bus driver has a day-in and day-out view of the planned bus route and bus stops and is in a good position to recommend changes, most district procedures call for the driver to seek supervisor approval for relocating a stop or changing a route rather than acting unilaterally.

Driver signal requirements: Defines specific communication between school bus drivers and students boarding or exiting the school bus, especially when students need to cross the road. The use of a standardized hand signal in such a situation should be used.

Frequency: Requirements or guidance that stipulate how close together stops may be placed on a route. Walkability to bus stops and the availability of waiting areas can dictate the need for more stops. For example, some state education policies indicate that stops should be at least .2 miles apart.

Location-based exceptions: Some local boards of education define specific location-based barriers that provide exceptions to situations where school bus transportation is provided, even if a student resides within the no-transport zone. For instance, the state may stipulate that transportation funding is not provided for students living within 2 miles of school. However, the local board may say that even inside those 2 miles, if a student must cross a road with four or more lanes to walk to school, the district will provide the student with transportation. Regardless of location, bus stops and travel paths to bus stops should be free of conditions that the local boards of education consider unsafe.

Mixed grades at stop: Stipulates which student grade levels (elementary, middle, high) are allowed to wait at a bus stop together.

Parent responsibilities: School district expectations regarding the parent’s involvement in the student’s access to and waiting at the bus stop. This can include talking points for parents to use when teaching their children about walking paths to stops. Parents may be required to be present at a stop with children of a certain age (e.g., up to second grade).

Right side pickups: Recognizing the danger to children when crossing the road to access the bus stop or to board the school bus, these types of policies encourage bus stops where students board on the right side of the bus and are supplemented by policies that stipulate circumstances that provide exceptions to such a requirement.

Route hazard identification: Documented process by which route hazards can be periodically identified and documented. Hazardous situations along a school bus route, such as road configuration and visibility, are typically known by the regular bus driver, but may not be known by a substitute driver.

School bus stop creation and stop review: Processes used in reviewing the locations of bus stops (responding to parent inquiries or complaints, or suggestions from bus drivers) and in creating new bus stops.

Special education and Individualized Education Programs: Processes to provide appropriate accommodations in school transportation. This involves providing students transportation in the least restrictive environment setting while recognizing that some bus stops may need to be at the end of or in students’ driveways.

Roadway Characteristics

The roadway on which a school bus travels affects the school bus route and the safety of students entering or exiting the bus at each stop. Similarly, the characteristics of a roadway can affect the safety of students as pedestrians traveling on, near, or by the roadway. Important characteristics include the following.

Speed Levels

Walking along or across high-speed roads (generally greater than 35 mph) should be avoided to reduce the risk of injury. The response of drivers approaching students may be slower with higher speeds and crash severity can increase with speed level. Similarly, bus routes on lower-speed roads may be deemed safer options than those on high-speed roads.

Stop in Right-turn Lane

A bus stop should be located so that the bus stops in the far-right lane of traffic, where vehicles turn to the right. Regardless of whether students are crossing, there should not be an active lane of traffic adjacent to the bus door when stopped. Additionally, some states require or encourage school buses to make stops off the road on the shoulder, when possible.

Note that there are exceptions to the “far-right lane rule,” such as in New York City where some buses have left-side service doors for picking up and dropping off students on one-way streets and will stop in the far-left lanes. Another exception is in a dedicated right-turn lane. Like acceleration/merge lanes, bus stops should be located 100 feet from a right-turn lane, especially if the bus will not be turning right at the intersection.

Lighting

Visibility for both bus and community drivers may be affected by the level and type of roadway lighting on a route. Because lighting levels may naturally shift by the time of day, visibility during both morning pickups and afternoon drop-offs should be considered when determining the locations of safe bus routes and stops. Lighting-related visibility across seasons and time changes should be incorporated as part of these considerations.

Traffic Flow

Along with speed, the traffic flow associated with a roadway is a key factor in the safety of a roadway associated with school bus stops and routes. Transportation departments should understand the level of traffic and consider that level (low, medium, or high) when establishing school bus stops and routes. Some school districts set different policies by grade, depending on the level of traffic.

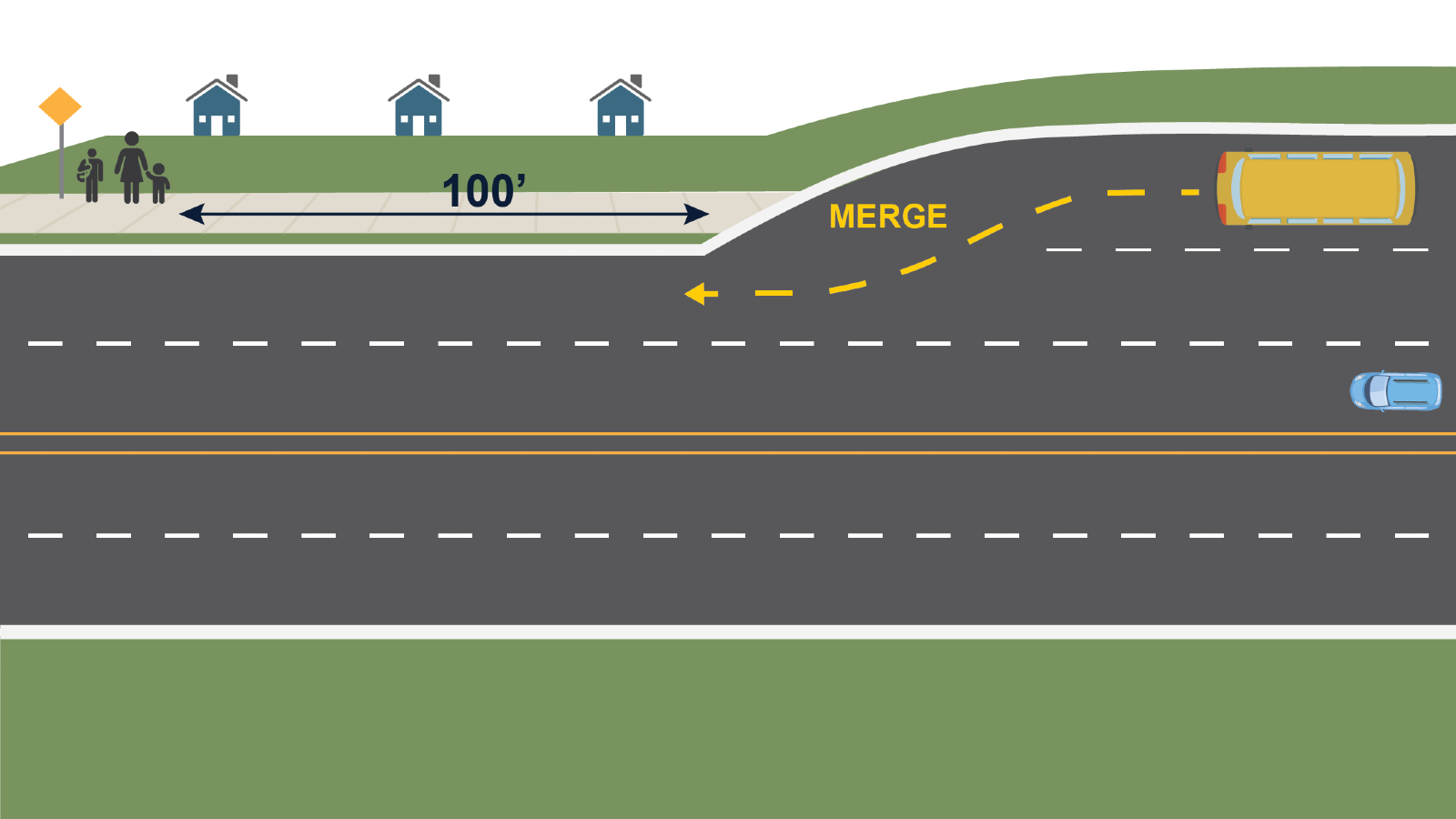

Merging and Upcoming Turns

Merge lanes, typically on higher-speed roadways, are designed to allow traffic to accelerate before joining a roadway or to decelerate before exiting a roadway. Bus stop waiting locations should be avoided next to these lanes and should be located at least 100 feet before or after this roadway configuration.

When a bus stop is placed at a location on a route that will often be followed closely by a left turn across several lanes of traffic, consider relocating the stop or rerouting the bus if possible. Otherwise, the bus must attempt a traffic maneuver that may be unexpected by other motorists, which can increase the risk of a collision.

While the bus stop above may be more central to all students if placed in front of the center house, the priority should be placing the stop farther from the merge lane.

Intersections

When roads intersect, the result is multiple corners or potential waiting areas. If the bus stop location is only designated at the general intersection, the specific location of the waiting area is unclear. Further, without knowing the direction of travel of the school bus, it cannot be known whether students would have to cross the street to board the bus.

“Placing a bus stop at an intersection creates conflict for cross traffic and understanding what to do at the bus stop. The school bus cannot be expected to control cross traffic when the lights only project to the front and rear. Secondly, if cross traffic turns onto the road where the bus is stopped, motorists need time to observe, react, and stop for the school bus.”

-LT. BRIAN REU, MINNESOTA DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC SAFETY, STATE DIRECTOR OF PUPIL TRANSPORTATION, PERSONAL COMMUNICATION, MARCH 23, 2022

Proximity of Stop

A bus stop should not be located at an intersection. Especially on a roadway with a speed limit greater than 35 mph, the bus stop should be located at least 100 to 200 feet from an intersection. When stops are located too close to intersections, then vehicles turning from the cross streets do not have time to respond quickly and safely.

To avoid confusion on the part of nearby motorists, particularly those turning onto a street where a bus will stop, school bus stops should not be located at intersections, especially on roads with speeds greater than 35 mph.

Traffic Control Devices

When students must cross busy streets to reach the school bus stop, this should be done so that students are afforded the protection of traffic control devices wherever possible. This is true at both intersections and midblock crossings.

Special Roadway Situations

Cul-de-sacs

School bus routes should avoid traveling into cul-de-sacs or dead-end roads where backing maneuvers will be required. If the road is so long that students are not permitted to walk out to the main road by policy, or if there are unique circumstances with the roadway, the district should do a thorough review of the bus stop placement in advance.

Road Maintenance

When possible, school bus routes should use roads that are well maintained. The maintenance authority should be consulted if unsafe conditions exist.

Private Roads

School bus routes must follow state and local policies for traveling on private roads. Often, this involves obtaining permission from the owners and sometimes proactive agreement on damage to the road caused by a school bus. Note that locating stops on some private roads (e.g., in a large mobile home park or apartment complex) has the advantage of keeping large numbers of students from the main road, which is typically a higher-speed and higher-traffic environment.

Mobile Home Parks and Apartment Complexes

When entrances to mobile home parks and apartment complexes are used as bus stop waiting areas, the specific location where students will gather must not be at the roadway entrance if vehicles frequently enter and exit at speeds greater than 5 mph.

Heavy Vehicle Usage

Bus routes, and bus stop waiting areas in particular, should avoid roadways used by heavy vehicle traffic or narrow roadways where it is difficult for two large vehicles (including school buses) to pass each other.

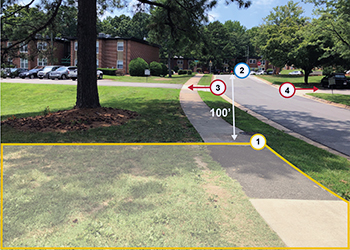

In this example, designating the bus stop waiting area (1) keeps students from the main road (2), and away from driveways on the left, (3) and right (4) where vehicles are likely to be moving, particularly during morning pickup periods.

Signage

A School Bus Stop Ahead sign alerts motorists of an upcoming school bus stop, often used when there are curves, hills, or other visibility impediments. Speed limit signs on roadways approaching a school bus stop waiting area offer the benefit of calling the motorists’ attention to the required speed. Requesting signage from local or state highway authorities should be done with discretion, recognizing that too many signs can blend into the landscape and escape motorists’ attention. See Helpful Resources for sign images and for information on coordinating with your state or local DOT for the installation of School Bus Stop Ahead signs.

The safest bus stop is one where students arrive at a waiting area – without crossing high-speed or high-traffic streets – and then board the bus that approaches in a direction where the students do not have to cross the street. As a result, bus stop locations that require students to cross the road to board the bus in the morning and after disembarking the bus in the afternoon should be minimized. Three factors contribute to a student crossing condition when students are entering or exiting a school bus:

- The location of the bus stop waiting area.

- Where the students assigned to the stop are coming from (e.g., student residence or other location from which the student will walk to the stop).

- The bus route, which will stipulate the direction of bus travel at the stop.

Sometimes, there are no options other than crossing. In these cases, considering several items may help improve safety.

THE NTSB ISSUED RECOMMENDATIONS TO NASDPTS, NAPT AND NSTA IN ITS REPORT OF THE ROCHESTER, INDIANA, CRASH INCLUDING THE FOLLOWING:

“Advise your members to train their school bus drivers and students in crossing procedures, including the crossing hand signal and the danger signal, which are to be used when a student roadway crossing cannot be avoided (H-20-17).”

Crossing Roadways at the Stop or as a Pedestrian

Children remain pedestrians while waiting at the school bus stop and boarding the school bus. Deciding which roads students are allowed to cross to access their bus stops is key to their safety. Several aspects of a student’s journey should be considered when planning his or her path to and from a bus stop.

Careful consideration should be made when determining which roads are safe for child pedestrians to cross to and from their bus stops. Illegal passing can be an issue.

Crossing multiple lanes

Crossing multi-lane roads increases a student’s risk of injury. Avoid bus stop locations that require students to cross roads of three or more lanes, both at the bus stop (under the care of the school bus stop arm) and walking to the bus stop waiting area.

Crosswalks, traffic control devices, and pedestrian signals

The presence of walk-friendly infrastructure like pedestrian signals and crosswalks can also enhance safety on roads. Similarly, when students must cross busy streets, it should be done in such a way that they are afforded the protection of traffic control devices. Avoid stop locations that require students to cross roads with three or more lanes while walking to the bus stops or boarding the buses.

Driver Signals

Where student crossings are unavoidable, it is critical to establish a standard procedure in which school bus drivers and students communicate and are each involved in proactive communication that promotes safe crossing and boarding.

Hand Signal

A standard driver hand signal is essential in all cases. While establishing a statewide driver hand signal is the most effective approach, in the absence of a statewide procedure, school districts should establish their own standard procedures and enforce their use as matters of policy. While the specifics of a driver’s hand signal may vary, North Carolina provides an example of what these signal procedures can look like:

A key element of driver-student communication is making sure that once the driver gives the signal students crossing on their way home from school look both ways before stepping into the open lane of traffic.

Emergency Horn

The use of the emergency horn signal is another tool drivers can use to help increase student safety. In the rare event that the driver signals students to cross and then sees a vehicle that is not going to stop, the only way to get the students’ attention is the school bus horn. Students must be taught – and it must be reiterated – that the horn is a danger signal that means “return to safety” or “get out of the road.” Parent and student educational campaigns can help share this information.

School bus safety education includes instruction on the danger zone as well as required crossing procedures, including obeying the driver’s signal and the appropriate response if the driver sounds the horn.

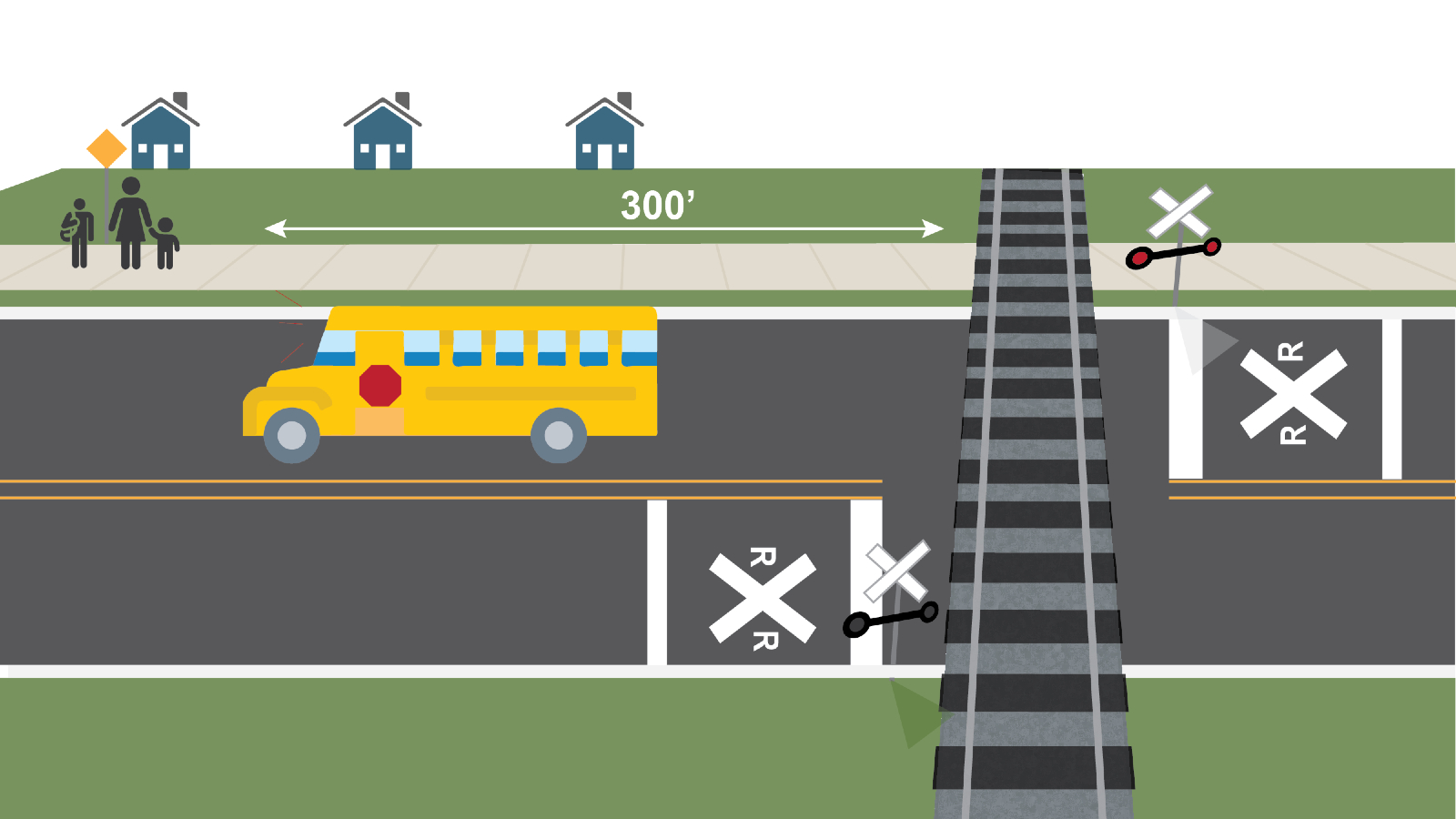

A stop should be located in an area that reduces risks associated with railroad crossings. Both exposure in the area surrounding the stop waiting area and during travel to the bus stop need to be reduced to provide a safer environment for students. The following factors should be considered when placing a bus stop.

Distance From Stop

The distance from an active railroad crossing should be maximized and at least 300 feet, if possible.

Warning Indicators

Bus routes are safer when the bus driver and other motorists are alerted about an upcoming crossing in time to take appropriate precautions. Signage (“Railroad Crossing” signs and pavement markings) should be clearly visible. If not, local or state highway officials should be contacted to help improve the safety of the area.

In the example above, the bus stop waiting area is not located central to the student residences; rather, it is located to be sufficient distance from the railroad crossing.

Track Visibility

Track visibility is a feature of a bus route rather than the location of a bus stop. When a school bus encounters a railroad crossing on its route and is stopped 15 feet from the nearest rail, there should be 1,000 feet of visibility down the tracks in both directions. If there are multiple parallel tracks, the driver should be able to see all tracks. The absence of these characteristics should be reported to authorities and documented as a route hazard to be provided to all drivers, especially substitute drivers.

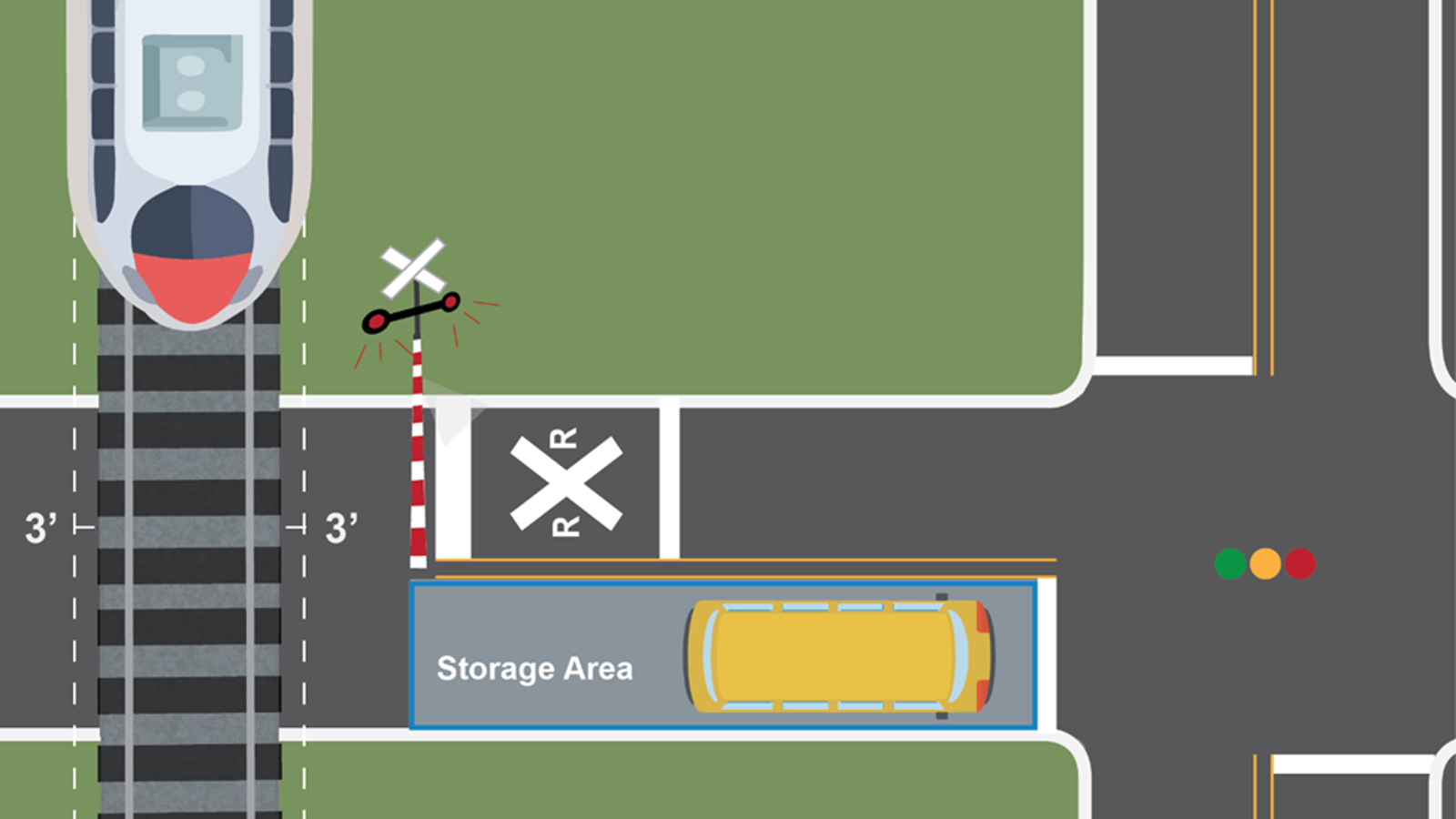

Storage Area

When a school bus crosses a railroad track at a grade crossing and then must stop (e.g., for a traffic signal), the driver must know that there is enough room for the school bus (known as the “storage area”) well past the farthest rail, recognizing that the train’s width extends at least 3 feet outside of the rails. If not, the bus may not cross until it can proceed without stopping. Such a situation must be documented as a route hazard to be provided to all bus drivers, especially substitute drivers.

“If it won’t fit, don’t commit.” The storage or containment area is the space on the other side of the railroad grade crossing between the tracks (plus the 3-foot overhang and a 10-foot safety buffer) and the traffic stop line when there is a traffic light or stop sign on the far side of the crossing.

Hazards on Bus Route

Route hazards should be identified and managed or avoided based on existing policy.

Hazard Types

Some route hazards are classified as variable, as they occur unpredictably (e.g., a falling tree or an animal crossing the roadway) and are best handled by school bus driver training and defensive driving. Other route hazards are constant, such as the stopping area available before a railroad crossing, or a bridge that is unusually narrow when two large vehicles approach from opposite directions. These constant hazards are typically known by the regular bus driver but may not be known by a substitute driver.

Route hazards like narrow bridges, should be avoided when possible. It is important to inform all bus drivers, especially substitutes, about such hazards.

Recommendations

The National Transportation Safety Board, in its investigation of the 1995 school bus-train crash in Fox River Grove, Illinois, included the following in its recommendations to the National Association of State Directors of Pupil Transportation Services:

- “Encourage your members to develop and implement a program for the identification of school bus route hazards and to routinely monitor and evaluate all regular and substitute school bus drivers.” (H-96-52)

- “Advise your members to consider railroad/highway grade crossing accident histories or unusual roadway characteristics when establishing school bus routes.” (H-96-53)

In response to recommendation H-96-52, NASDPTS created a guide to be used by school districts in identifying and documenting route hazards. This guide is referenced on the Helpful Resources page.

Hazards Near Bus Stops

Some hazards can also be problematic if they are located near a bus stop. The following are examples.

Commercial Driveway Entrances

Entrances to commercial areas (e.g., shopping centers) or apartment complexes where traffic would travel more than 5 mph should be considered as potentially hazardous because of turning vehicles. When a stop is placed near such an entrance, it should be placed at least 100 feet from the entrance.

Drainage and Snowbanks

Student exposure to areas with poor drainage, resulting in standing water, should be minimized. Seasonal precipitation-related issues such as snowbanks and snowmelt should also be considered when avoiding exposure to potential safety hazards.

Construction

Student exposure to areas of ongoing road construction (or other large construction projects extending near the road) should be minimized.

Student exposure to construction areas can present risks that should be minimized.

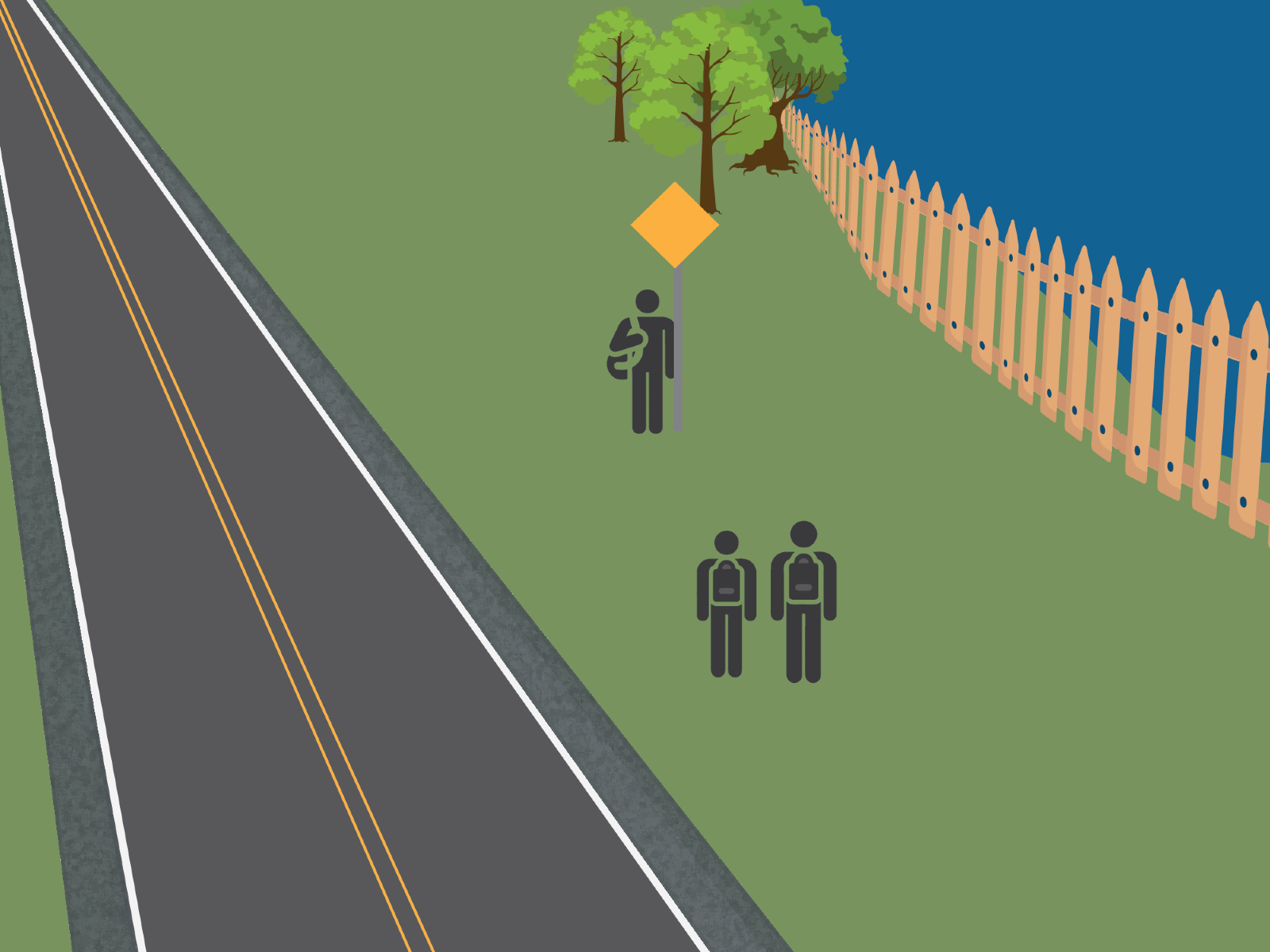

Bodies of water

If a bus stop waiting area is near a body of water, the waiting area should be separated from the body of water by a barrier. Ask, “Is there a physical barrier between the stop and the water, for example a guardrail or fence?”

A bus stop waiting area should not be adjacent to a body of water without a barrier such as a fence or guardrail.

Consideration of student safety should extend beyond the risk of injury due to a vehicle crash (e.g., exposure to dangerous animals or wildlife).

This applies to both the path a student takes to reach a stop and the stop waiting area itself. It may be impossible for a student to reach the bus stop without passing by some of these areas, but efforts should be made to reduce risks. While some areas may be deemed safe to move through as a pedestrian or bicyclist, bus route and stop decision-makers should consider which spaces are also safe for a student to wait for an extended period of time.